|

|

Witch Caves & Salem End Road

Framingham Massachusetts

Field Investigation:

25 November 2001, 26 May 2007, & 1 June 2007

by Daniel V. Boudillion

|

Note: this is the full

text of the abbreviated version published in the book Weird Massachusetts

Introduction

Salem was a dangerous and

unforgiving village in 1692. The Witch Hysteria was in full swing

and the simple pointing of fingers was all it took for 19 men and women

to lose their lives at the end of the hangman’s rope on Gallows Hill.

The shadow of the rope fell

particularly harsh on the daughters of William Towne of Topsfield. All

three sisters were soon accused of witchcraft and jailed. Only one made

it out alive. She escaped to Framingham and lived in inhospitable caves

for a winter – Witch Caves –

forming an expatriate community the following spring with other refugees

in a place named after them: Salem End Road.

From Topsfield, to

Salem’s Court, to Salem End Road. The caves are empty and cold now.

Yet the houses they built the following years in Salem End still stand,

and their names woven deep into the community as the years passed:

Nurse, Easty, Cloyes, and Towne.

It was a dangerous time. This

is their story.

Witch Hysteria: A Brief History of the "Sport"

First, a brief

outline of the Salem Witch Hysteria will help keep the story in the

wider context. An important initial point to know is that Salem Town

and Salem Village were two different, though adjacent, worlds. One was

a small thickly-settled seaport town, busting with commerce, the other a

large rural area of farms and woodlots. The witch hysteria almost

exclusively took place in Salem Village (see

map &

index), renamed the Town of Danvers in

1752. First, a brief

outline of the Salem Witch Hysteria will help keep the story in the

wider context. An important initial point to know is that Salem Town

and Salem Village were two different, though adjacent, worlds. One was

a small thickly-settled seaport town, busting with commerce, the other a

large rural area of farms and woodlots. The witch hysteria almost

exclusively took place in Salem Village (see

map &

index), renamed the Town of Danvers in

1752.

The Reverend

Samuel Parris was the minister of Salem Village. His household included

a West Indian slave named Tituba who was often given the task of

overseeing the two young girls. During the long winter of 1691–1692,

she regaled the two girls, Elizabeth Parris, nine, and her cousin

Abigail Williams, 11, with tales of her girlhood in the Barbados. The

stories were so entertaining that soon the girls invited their friends

to the kitchen hearth to join in. Soon a regular little group was

meeting and as the conversations began to revolve around Tituba’s

knowledge of forbidden subjects such as voodoo and fortune telling, it

became an exciting adventure.

Samuel Parris Parsonage: excavated

foundation on left, structure in 1892 on right

Danvers

Elizabeth began

having seizures and uttering strange noises early in January of 1692,

followed closely in this by the older Abigail. Alarmed, Parris called

Dr. Griggs, who declared in mid-February that the girls were "under

the evil hand."

Thus the idea that witches were afoot in Salem Village was introduced

for the first time. After repeated demands by Parris for the girls to

name the witches responsible, they named Tituba, and two unpopular

women, Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne. When questioned, Tituba said Good

and Osborne were witches and been one with them until she changed her

ways.

Other Salem

Village girls began complaining of being "afflicted"

by witches and soon a group of ten girls were actively involved as the

primary litmus test of "witchcraft."

If they convulsed in the presence of a person, that person was a witch.

In short order fingers were pointed and the accusations began rolling

out in earnest by March 12, 1692, resulting in arrests, trials, and

ultimately executions. "Sport,"

the girls afterwards said of it, "we

must have our sport."

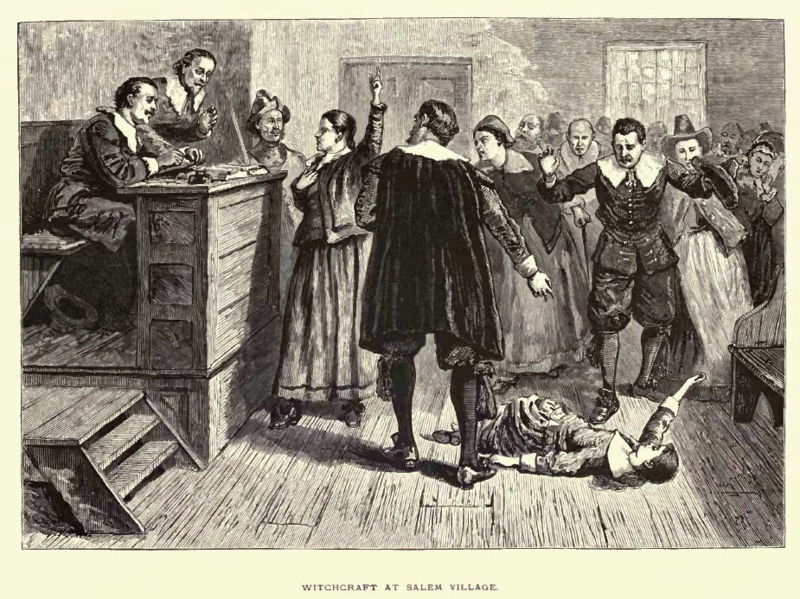

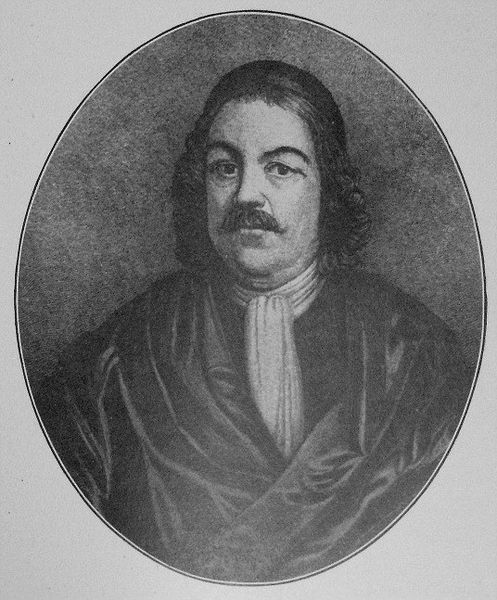

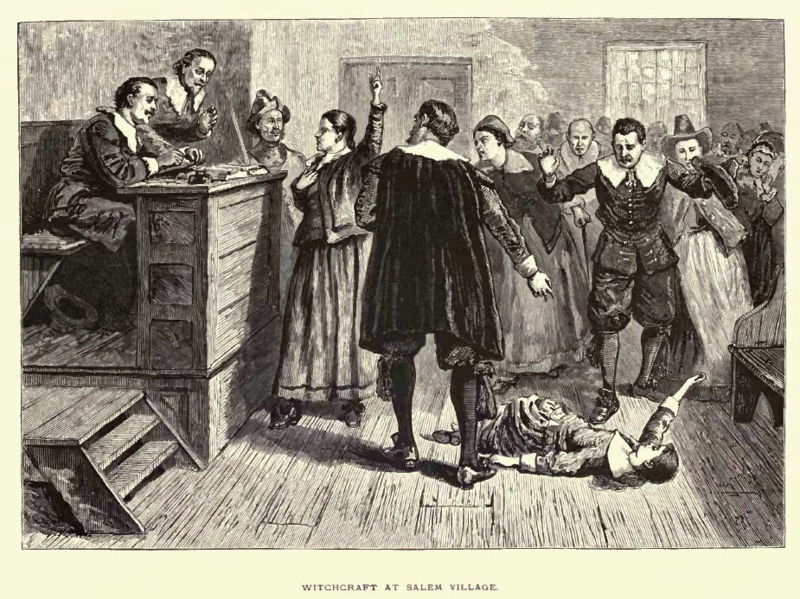

"Trial of George Jacobs, August 5,

1692"

Thomkins Matteson, 1855

Their sport became

the highlight of the trials, as did describing invisible events. This,

called "spectral

evidence,"

was the sole evidence that sent their neighbors to slow death in the

hangman’s noose.

A Grand Conspiracy Unmasked

The Towne sisters story begins

in Topsfield. Let’s commence by painting the witchcraft picture via

another Topsfield family, the Hobbs, William, Deliverance, and daughter

Abigail. All three were accused and brought to trial. Both Deliverance

and Abigail confessed. Abigail, an odd girl by all accounts, confessed

quite willingly and with obvious relish. The Towne sisters story begins

in Topsfield. Let’s commence by painting the witchcraft picture via

another Topsfield family, the Hobbs, William, Deliverance, and daughter

Abigail. All three were accused and brought to trial. Both Deliverance

and Abigail confessed. Abigail, an odd girl by all accounts, confessed

quite willingly and with obvious relish.

Deliverance’s confession in particular shook

Salem Village to its very roots. According to her, there were "some

three hundred of more witches in the county and that their object was

the destruction of Salem Village."

These were frightening words - the worst Puritan fears realized. Rage,

horror, and alarm followed this confession.

William Barker of Andover

confessed that "the Devil’s design was to destroy Salem Village …

to begin at the minister’s house … and to destroy the Church of God and

set up Satan’s Kingdom."

(Oddly, there actually is a "Satan’s

Kingdom" in Massachusetts, two of

them in fact: one in Westwood and a second in Northfield.)

A further outrage is that this

diabolical conspiracy held its meetings in their minister’s fields.

Deliverance’s daughter Abigail, who had "had sold herself body and

soul to the Old Boy," filled in the details to a hushed and anxious

audience. She described a "witch meeting, in the field near Mr.

Parris's house," in which Mr. Burroughs, a former Salem Village

minister, acted a conspicuous part.

"Witch Grounds" near the Parris

Parsonage

Danvers

She swore that "Mr. Burroughs

had a trumpet which he blew to summon the witches to their feasts" and

other meetings "near Mr. Parris's house." This trumpet, according to

her, had a sound that reached over the country far and wide, sending its

blasts to Andover, and wakening its echoes along the Merrimack, to Cape

Ann, and the uttermost settlements everywhere. The witches would

hearing this, would mount their brooms and fly to Mr. Parris's orchard,

just to the north and west of the parsonage.

Its sound was not heard by any ears other than those who were

confederates with Satan.

Ingersoll Ordinary: Where the accused

were first brought

Danvers

Revealed was the

Devil’s secret war, the very point and center of it being Salem

Village. The very Colony and Puritanism was at stake in a grand

conspiracy against God and man.

"The horror, alarm and rage

which must have followed such confessions can only indeed be imagined by

those who know the religious tendencies and convictions of the Puritans

at that day."

Being aghast with these revelations, and in

the grips of hysteria, it is no wonder that when the Towne sisters were

dragged into court, their pleas were given little heed and their fates

sealed from the moment of their arrest. They had been accused

(tantamount to a confession in the strange ways of Puritan courts of the

time) and thus were traitors, working destruction against God and God’s

community on earth.

It would prove to be a remarkable and ghastly

year. "Silence,

darkness, mystery, diabolism - all brooded over it and lent their aid."

The Daughters of William Towne

William Towne and his wife

Joanna emigrated from Great Yarmouth, England, to the Bay Colony

sometime between 1634 and 1639, settling on Main Street in Topsfield,

Massachusetts. They had seven children, four of them daughters. The

eldest daughter married and remained in England, but the two younger,

Rebecca and Mary, emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony with their

parents. The youngest, Sarah, was born in Topsfield in 1642.

William was a small farmer in a rural frontier

town to the northwest of Salem Village. The sisters were raised in the

family house located near the intersection of South Main Street and

Salem Street.

William Towne Homesite, Main Street,

Topsfield

William passed away in 1672 and

their mother Joanna died in 1682. Both were buried in Pine Hill

Cemetery but no markers remain. When the estate was settled in 1683,

the land was divided equally between the sons, John, Jacob, and Joseph.

The "moveables" were divided equally between the three

daughters.

In 1692, all three Towne sisters

lived along the road that traversed through Salem Village, from Salem

Town to Topsfield, known as High Street in Topsfield. Rebecca and Mary

were in Salem Village, Rebecca near the Salem Town line, and Mary near

the Wenham line. Sarah lived in Topsfield near the center of town.

Rebecca Nurse

The eldest daughter, Rebecca, or Rebecka as

she spelled it, was born in Great Yarmouth, England, in 1622. She

married Francis Nurse, another English immigrant, in 1644, when he was

26 and she was 22 years old. For the next 30 years they lived in a

small way in one of the most thickly settled parts of Salem Town, on the

Wooleston River neck near where the old ferry (and now bridge) crosses

to Beverly. (Number

95 on Upham Map)

Francis was a tray maker and

artisan by trade, but like most people of the time, he also worked a

small farm as well. At age 60, in an amazing stoke of good fortune and

sharp dealing, he managed to acquire the

300-acre Bishop Farm in Salem Village for no money down. In one

fell swoop in 1678 he went from a small farmer and artisan to one of the

largest land owners in the area. The Nurses took proud possession of

the lands and the large saltbox house, which still stands today and is

known as the Rebecca Nurse house.

Rebecca Nurse house

Danvers

The witchcraft

hysteria had started in the household of Reverend Samuel Parris, a

controversial figure in Salem Village for a number of years, around whom

political factions swirled. The fault lines of the hysteria seemed to

revolve around loyalty to Parris or

displeasure with

him. One group, became the accusers, the other, the displeased,

becoming the accused.

Indeed, so bitter had the

ministerial issues become that in 1691 the Nurse family began "absenting"

themselves from Sabbath meetings in protest. This was a move that did

not reflect well on them in the following year. Indeed, so bitter had the

ministerial issues become that in 1691 the Nurse family began "absenting"

themselves from Sabbath meetings in protest. This was a move that did

not reflect well on them in the following year.

In 1692, at the time of the

accusations, Rebecca was 71 years old, a respectable and even saintly

grandmother who had raised eight children. However, on March 23, a

warrant for her arrest for practicing witchcraft was issued and on the

following day she was arrested and dragged form her sickbed to the cold

stone prison in Salem. She was then transferred to a similar prison in

Boston. Petitions were signed on her behalf to no avail, and she was

transferred back to Salem for trial in May. She was found not guilty by

a jury, but so unhappy was the Chief Judge that he asked the jury to

reconsider. Abigail Hobbs, the self-proclaimed young witch, remarked

upon the not guilty verdict, "What? She is one of us." The

next verdict came in guilty.

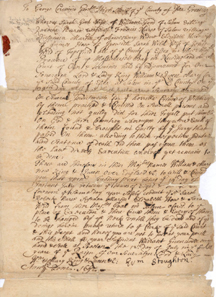

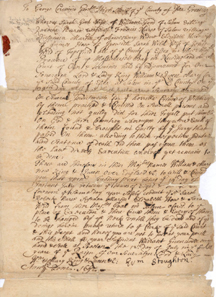

Rebecka Nurse Death Warrant

Rebecca in 1692, was

excommunicated and sentenced to death. A reprieve was granted, then

denied. On July 19, she was publicly hauled in a cart from Prison Lane

in Salem (now St. Peter’s Street), down Essex and Boston streets, and

over Town Bridge. There on a low rocky hill, she was hanged by the neck

until dead.

Gallows Hill, Salem

There were no gallows. She was

simply stood on the back of the cart, the rope slung over a tree limb

and around her neck, and the cart driven out from under her. It is

recorded that the Salem witch hangings were slow agonizing deaths of

asphyxiation. Friends and family members would pull on the victims legs

to help bring about a speedy end.

Crane Creek & Nurse Farm Cemetery,

Danvers

Denied a proper burial, she and

the others hung that day were dumped in a crevasse on the side of the

little hill. That night, her youngest son Benjamin, who was living at

the Nurse homestead with his pregnant wife, retrieved his mother’s body

by boat and rowed her back to the Nurse farm via Crane Creek where she was buried that

night in a secret grave. Back then, the North River was a wide bay, and

the water extended to the ledge behind the present day location of

Walgreen’s near where the hangings took place.

|

Gallows

Hill: Where Were the Witches Really Hung? by D. V.

Boudillion Gallows

Hill: Where Were the Witches Really Hung? by D. V.

Boudillion

The story of 18 people

accused as witches in the 1692 Salem Witch Hysteria ends as victims at

the end of a hangman’s rope on Gallows Hill, otherwise known as Witch

Hill or Witchcraft Hill. You would think such a public and awful

event at that spot would have made such a huge impression on people that

the location would live forever if only in infamy. Yet today, the exact

location of the hangings, and even which hill is Gallows Hill, is not

precisely known.

The town of Salem did set aside

a public park but there is still historical debate about the location of

the site and the clues lead elsewhere. Let us see where those clues

lead. . .

To read the entire

article,

click here.

|

To add insult to injury, the families of the executed were billed for

all the prison and execution costs, including leg irons and the

hangman’s fees. No food or bedding was given to the prisoners other

than what their friends and families could provide them.

Mary Easty

The middle sister, Mary Easty

(also recorded as Esty) was born in Great Yarmouth, England, in 1634.

She married Issac Easty of Topsfield in 1655 at the age of 21. They had

nine children and lived across the street from her parents in Topsfield

near the center of town. Issac was a well known figure in town and had

served as Selectman. (Number

2 on Upham Map)

Issac & Mary Easty Homestead site,

Topsfield

In 1692 Mary was 58 years old.

Within a few days of her eldest sister Rebecca’s arrest on March 23, her

younger sister Sarah was arrested as well. It was only a matter of time

before the fingers started pointing at the third Towne sister. On

April, 22 Mary was arrested in her

Topsfield home and held for trial in Salem Town. There was uncertainly

about her guilt and she was released on May 18th and returned

home, however, her homecoming was brief. She was arrested again on May

20th from her son’s house in Topsfield on what was

thenceforth known as Witch Hill and was dragged off in irons in the

middle of the night.

Witch Hill in Topsfield

In a sad turn of events, her

grandniece Rebecca Towne, who was 24 at the time, became one the "afflicted

girls" who testified against her in court. Rebecca was Mary’s

brother John’s granddaughter. Rebecca Towne also testified against her

other grandaunt, Sarah Cloyes as well. Both Rebecca’s father and

grandfather had passed away well before the trials; her father died when

she was only 10 years old. Perhaps this shameful act would not have

occurred had either men been alive.

Like her elder sister, Mary

Easty was convicted. She was hung to death on the low rocky hill on

September 22, in what is recorded as a "chill and rainy" day.

Sarah Bridges Cloyes

The youngest Towne sister, Sarah

Bridges Cloyes (also recorded as Clayes)

was born in Topsfield in 1642. She married Sargeant Edmund Bridges of

Topsfield in 1659 at age 17. Edmund, a lawyer, was part owner of a

wharf on the Salem waterfront and had also procured a license to sell

alcohol. According to McMillen, "Sarah became

involved with running the waterfront tavern while her husband carried on

with his legal practice, often appearing in Salem quarterly courts as

attorney, arbitrator and witness." The Bridges lived in Salem Town and

had 7 or 8 children, but Edmund died 1682 at the disappointing

age of 45. This was a difficult year for Sarah as both her mother and

husband died. The youngest Towne sister, Sarah

Bridges Cloyes (also recorded as Clayes)

was born in Topsfield in 1642. She married Sargeant Edmund Bridges of

Topsfield in 1659 at age 17. Edmund, a lawyer, was part owner of a

wharf on the Salem waterfront and had also procured a license to sell

alcohol. According to McMillen, "Sarah became

involved with running the waterfront tavern while her husband carried on

with his legal practice, often appearing in Salem quarterly courts as

attorney, arbitrator and witness." The Bridges lived in Salem Town and

had 7 or 8 children, but Edmund died 1682 at the disappointing

age of 45. This was a difficult year for Sarah as both her mother and

husband died.

Even worse, three months after her husband’s death, "The widow of

Edmund Bridges and her children were ordered out of Topsfield by the

constable, September 12, 1682." We don’t know why they were

ordered out of Topsfield but it is reasonable to assume that in an

impoverished condition she had returned to her family there after the

death of her husband in Salem Town.

Sarah quickly remarried to Peter

Cloyes in 1682, at the age of 40, a second marriage for them both.

Although records differ, it is believed they had either no children, or

none who survived to adulthood. They lived on Peter Cloyes’s farm in

Salem Village near Wenham. (Number

43 on Upham Map)

In 1692, Sarah was 50 years

old. The Cloyes were members of the Salem Village congregation of Rev.

Parris. Like the Nurse family, the Cloyes were also displeased with

issues revolving around the Parris ministry and by 1692 were also "absenting"

themselves from Sabbath. On April 3rd, Sarah walked out of a

sermon by Parris when he announced his text as, “Have

not I chosen you Twelve, and one of you is a Devil.” The wind caught

the door as she left, slamming it.

The following day

a complaint of Witchcraft was brought against Sarah, and she was

arrested on April 8th. She was examined and refused to

confess. She was fitted with hand and leg irons and placed in

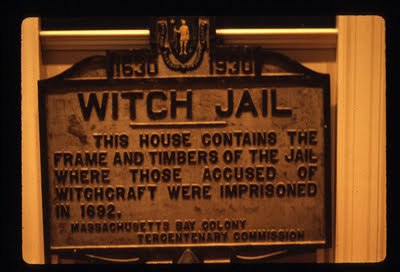

Salem

jail with her sister Rebecca. Later she was removed to a Boston prison,

and then with her sister Mary to Ipswich, and then back to Salem again. The following day

a complaint of Witchcraft was brought against Sarah, and she was

arrested on April 8th. She was examined and refused to

confess. She was fitted with hand and leg irons and placed in

Salem

jail with her sister Rebecca. Later she was removed to a Boston prison,

and then with her sister Mary to Ipswich, and then back to Salem again.

Two weeks after

Rebecca’s execution in July, a charge of 20 pounds sterling was

presented by the blacksmith "for

making fouer payer of iron ffetters and tow payer of hand Cuffs and

putting them on to ye legs and hands of Goodwife Cloys."

Sarah’s grandniece

Rebecca Towne testified against her, just as she testified against Mary,

and an indictment followed. "On the following day an indictment was

made out against Sarah Cloyes, wife of Peter Cloyes of Salem, in the

County of Essex, husbandman, that 'in and upon the ninth day of

September --- in the year aforesaid and divers other days and times as

well before as after, certain detestable arts called witchcraft and

sorceries, wickedly, maliciously and feloniously hath used practiced and

exercised... in, upon and against one Rebecca Towne of Topsfield in the

County of Essex aforesaid Rebecca Towne... was and is tortured,

afflicted, consumed, pined, wasted, tormented, and also for sundry other

acts of witchcraft by the said Sarah Cloyes."

Arresting a Witch, by Howard Pyle, 1883

Mary was executed in September

two weeks following Sarah’s indictment, as the wheels of injustice

remorselessly ground away.

However, unlike her elder

sisters Rebecca and Mary, Sarah’s husband did more then just gape at

their "witch" wives in amazement at the trails. Peter was

truly devoted and toiled diligently for her release. Danvers Church

records note his devotion to her that summer:

"......Brother Cloyse hard to be found at home being often with his wife

in Prison in Ipswich for Witchcraft...."

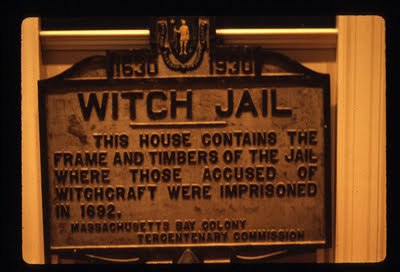

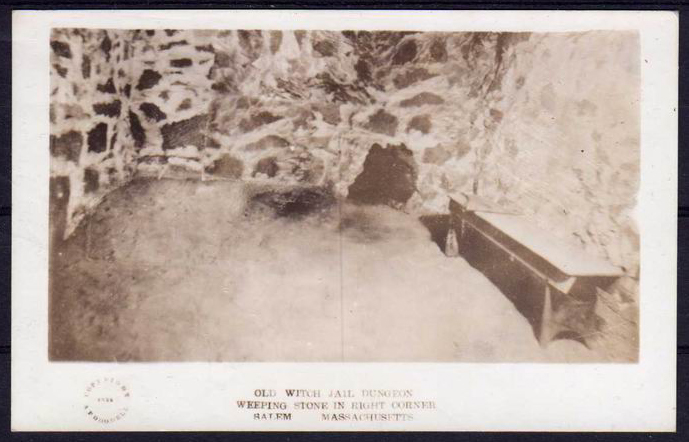

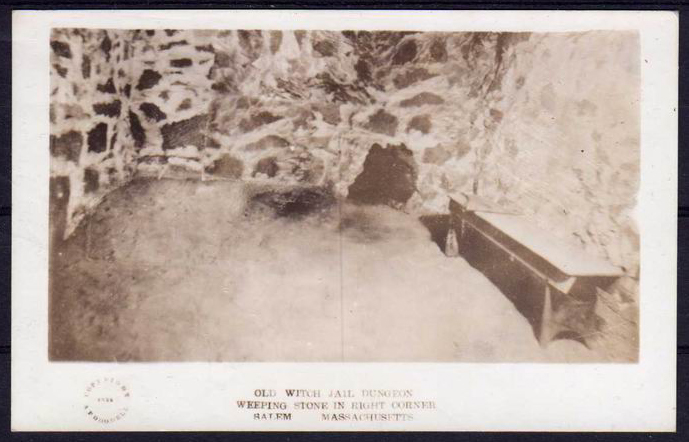

Old Witch Jail Dungeon

Weeping Stone in Right Corner

Salem Massachusetts

When all the legal

maneuvers failed, with Sarah’s sisters having been hung as witches,

Peter did the only intelligent thing as the shadow of the hangman’s rope

drew near in the new round of trials of January 1693. He broke Sarah

out of jail and fled south.

Escape & Flight

First, we have to acknowledge that the Daily

News Record in 1993 claims that in early January of 1693, that the

Superior Court dismissed the charges against Sarah; Peter simply paid

the prison fees and she was released. Following this they moved to

Marlborough, according to the paper.

But tradition and earlier

reliable sources tell us otherwise. According to the book

Framingham Historical Reflections, "Clayes was imprisoned in Ipswich and

smuggled out along with friends who had come to visit her," and

thence, according to the History of Framingham, "conveyed by night

to Framingham." But tradition and earlier

reliable sources tell us otherwise. According to the book

Framingham Historical Reflections, "Clayes was imprisoned in Ipswich and

smuggled out along with friends who had come to visit her," and

thence, according to the History of Framingham, "conveyed by night

to Framingham."

Framingham historian Stephen

Herring adds in 1999 that "it’s known that she somehow

escaped from a makeshift ‘jail’ in Ipswich – probably a farmer’s shed –

and made her way with her husband towards

Danforth’s property," a safe area in what is now

Framingham.

Certainly Peter

had been petitioning for a recognizance for his wife and it is always

possible they simply skipped bail.

Old

Connecticut Path, Westborough, Massachusetts

However they managed Sarah’s escape, it was

deep in a New England winter that they made their way southwest to

Framingham, then known as the Danforth Plantation, and marked in old

records of the times as "the

wilderness."

This is full 40 miles as the crow flies, but they did not undertake such

an unlikely journey on speculation. They knew somehow they had a safe

(albeit cold) haven waiting at Danforth Plantation in the wilderness.

Perhaps the friends that helped smuggle Sarah out were part of a wider

but fledgling "underground

railway"

out of Salem.

The only cross-country roads in 1693 were the

early bridal paths which followed the old Indian trails. The only such

path going southwest towards Framingham was the

Old Connecticut Path.

This wound its way from Watertown southwesterly through the wilderness

lands until eventually reaching the shores of the Connecticut River near

Hartford. Peter knew Old Connecticut Path, having grown up in

Watertown. It was the main path southwest. In fact, it was the only

path southwest. He had probably walked the eastern end extensively as

young man.

Old Connecticut Path

Trailhead just Northeast of Boston at

Watertown, Danforth Plantation is marked in Green

click to

enlarge

The Cloyes would have carefully picked their

way to Boston by night, avoiding encounters. It is unlikely they would

have been able to manage this portion of the trek without the assistance

of the friends who helped smuggle Sarah out of Ipswich jail. For one

thing, Sarah wasn’t well.

Having reached Boston safely, they would have

gone west to Watertown and picked up the trailhead of the Old

Connecticut Path. The Cloyes traveled this path southwesterly for about

ten miles, entering the eastern side of the new Town of Sudbury (now

Wayland), following the lower contour of Reeve’s Hill, well above the

icy wet river meadows, and then crossing the frozen Cochituate Brook at

the ancient wading place. Shortly thereafter they would have entered

what is now the northeast corner of Framingham, crossing the Sudbury

River at an ancient fordway, and then preceding southwest, a five mile

journey as the crow flies from Wayland.

Pout Rock & ford on the Old Connecticut

Path

Sudbury River, Ashland

Up to about 1690

the earliest settlers of the Danforth Plantation built on or near the

Old Connecticut Path, so not long after fording the Sudbury River, the

Cloyes would have seen the welcoming lights of several existing

homesteads. Or perhaps not so welcome. Sarah was a condemned witch

from a proven witch family – a notorious consort of the devil - and her

husband an accomplice in her escape. Criminals both, they probably

swung clear through the cold of the harsh winter night. Better to wait

until spring and official grace

from

Danforth himself before showing themselves.

Refuge at the Danforth Plantation

It’s a strange thing, but

Danforth Plantation

where the Cloyes sought asylum was owned by one of the early Judges at

the Salem Witch Trials. Deputy Governor Thomas Danforth had sat on the

early Tribunal. But he had left the tribunal in May, several months

before the hangings began, harboring a secret disgust and ill-ease with

the proceedings. In fact, Judge Sewall, a prominent witch trial judge,

wrote in his diary that Danforth had done much to put an end "to

the troubles under which the country groaned in 1692."

It may also be that Danforth’s departure from

the tribunal in May might have to do with the fact that he was Deputy

Governor under Governor Bradstreet, and the Governorship changed hands

to Sir William Phips on May 14, 1692. He may simply no longer have had

the position or authority to sit on the tribunal. Judging by his later

actions, this may have been a disastrous loss for the accused.

Sir William Phips & Governor Simon

Bradstreet

Danforth had acquired at least

16,000 acres of land in Colonial government grants between 1660 and

1662. This was originally known as Danforth Farm or Plantation, and

later renamed Framingham. In a 1999 newspaper

article, Herring is quoted as saying he believes that Danforth was the

secret "guardian angel"

who helped the Cloyes, and more than a dozen other escaping Salem area

families who were "all related by

blood or marriage," to find refuge

on his Plantation.

Danforth subsequently turned over more than

800 acres to Salem families seeking asylum and safety, including the

Towne, Nurse, Bridges, Easty, and Cloyes families. The new settlement

quickly became known as Salem End Road. They came fearing for their

lives, seeking a safe haven, and found it on Danforth’s Plantation,

living in safety on his land as a reparation for their treatment in

Salem.

The Cloyes’ escape and deliberate journey to the Plantation, the

subsequent steady arrival of Salem Witch Trial refugees and the awaiting

farmland, all smacks of a shadowy hand moving behind the scenes, and a

loose network of helpful friends. In short, there are glimmers of a

primitive "underground

railway"

in operation, quietly moving Towne sisters and related families out of

Salem Village to a more hospitable locale. The Cloyes’ escape and deliberate journey to the Plantation, the

subsequent steady arrival of Salem Witch Trial refugees and the awaiting

farmland, all smacks of a shadowy hand moving behind the scenes, and a

loose network of helpful friends. In short, there are glimmers of a

primitive "underground

railway"

in operation, quietly moving Towne sisters and related families out of

Salem Village to a more hospitable locale.

Danforth had been on the Tribunal through May, long enough to have

observed the character of all three Towne sisters. Records show that

the three sisters repeatedly behaved with dignity, piety, firmness and

good character to such an extent that the magistrates hesitated

repeatedly with their cases. Rebecca was brought in Not Guilty, only to

be re-deliberated until Guilty. She was reprieved, only to have it

denied. Petitions were signed on her behalf. Mary was cleared only to

be re-accused and rearrested. The minister of Topsfield vouched for

both Mary and Sarah, but to no avail. Sarah wrote elegant appeals that

were ignored.

It seemed the fates were blindly determined that they should die

regardless of the laws of man and god. Many were rightfully impressed

with the Towne sisters and deeply distressed with the proceedings.

Danforth seems to have been one of those and afterwards made it his

business to take in and see to the welfare and reparations of the

surviving Towne sister’s families, starting with Sarah (Towne) Cloyes

herself. Ironically, in Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible, Danforth

was unflatteringly portrayed as a "Black-robed

paragon of Puritan rectitude."

However it was

that the Danforth haven become known to those fleeing the accusations

and executions, a large boulder on Salem End Road was said to be the

official landmark that that signaled escaping families that they were on

the Plantation and safe at last.

Boulder marking Danforth Plantation

Salem End Road

A Cold Winter in the Rocks

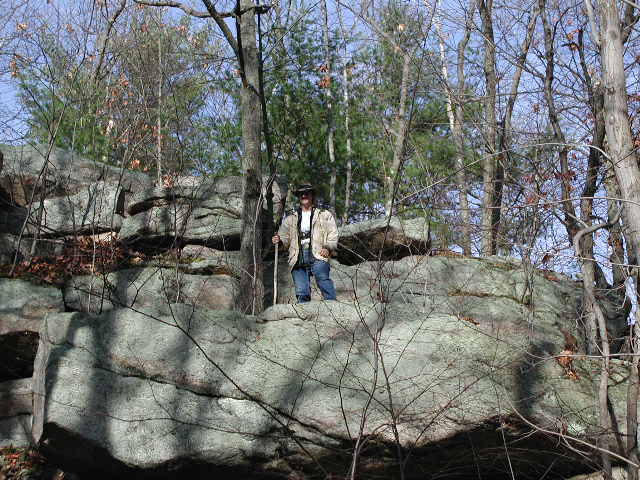

It is unknown exactly where the

Cloyes spent that first bitter winter in Danforth Plantation. But local

legend has always claimed it was in a network of small boulder caves in

a steep cliff face (Witch Cliffs) on the Framingham-Ashland

line. These caves have always been called Witch Caves. (GPS

coordinates: 42.27630N, -71.46930W.)

I have explored

these caves twice; once in 2001 and more recently in 2007. One thing I

can assure above anything else is that these caves are small, cold,

drafty, and hard. Little improvement over the stone cell of Salem Town

Prison. Of course, I am sure they would have blocked the holes tight

with snow, stuffed the place full of leaves, made spruce-bough beds,

built a lean-to of logs in front of the entrance, and made a door flap

with birch bark. That’s pretty much what any outdoorsman would do faced

with such a situation. Add a fire under the lean-to, and it’s a slight

much better, and warmer, than you might expect. Peter Cloyes had been

an Indian fighter in the 1675-76 King Philip’s war and lived in Wells,

Maine, and was likely a rough and tumble woodsman of necessity. I don’t

think he would have had much trouble turning the caves into a snug

burrow for the winter.

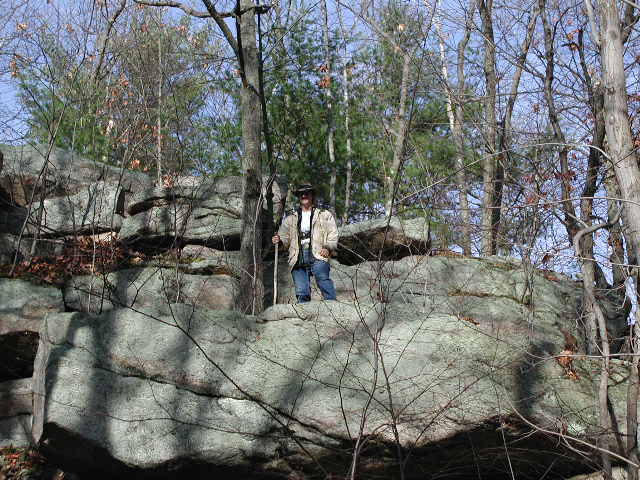

Witch Caves in Witch Cliffs ~ Looking

out of a Witch Cave across the ravine.

Ed Cornish on Witch Cliffs November

2001 ~ looking down from top of Witch Cliffs June 2007.

The Author at Witch Caves & Cliffs

November 2001

Sarah was hardly

in good health when she escaped Ipswich. She was 50 years old, and had

spent nine months in

various jails routinely shackled in irons, in unheated quarters,

subsiding only on what her family was able to provide her. She emerged

from jail that cold winter night a sick and fragile woman. She was very

lucky to have survived the ensuing winter in the caves.

Interior of Witch Caves in Witch Cliffs

In the 1985 PBS mini-series

Three Sovereigns for Sarah, it is argued that she only survived her

imprisoning because five months of her term was in Ipswich, a makeshift

private affair in an old barn, not the ghastly Colonial stone cells of

Salem and Boston.

Other Escapees: Nahant and Rockport

The Cloyes weren’t the only ones

that thought to get of Salem Village fast and caves seem to have been a

popular hideout. For example, in Nahant there is a low boulder-stone

cave, more like a chamber really, locally known as the

Witch Cave. Robert Ellis Cahill, the

former Sheriff of Salem, reports in Ancient Mysteries that it is where a

woman accused of witchcraft supposedly hid with her daughter in 1692.

The name of the woman is not recorded.

Another mystery escapee – this

one recounted in Skinner’s Tales of Puritan Land in 1896 – is the "blue-eyed

maid of Wenham, whose lover aided her to break the wooden jail and

carried her safely beyond the Merrimac, finding a home for her among the

Quakers." I have searched the records and am unaware of any woman

from Wenham who was accused of witchcraft let alone jailed. But it’s a

nice story nonetheless.

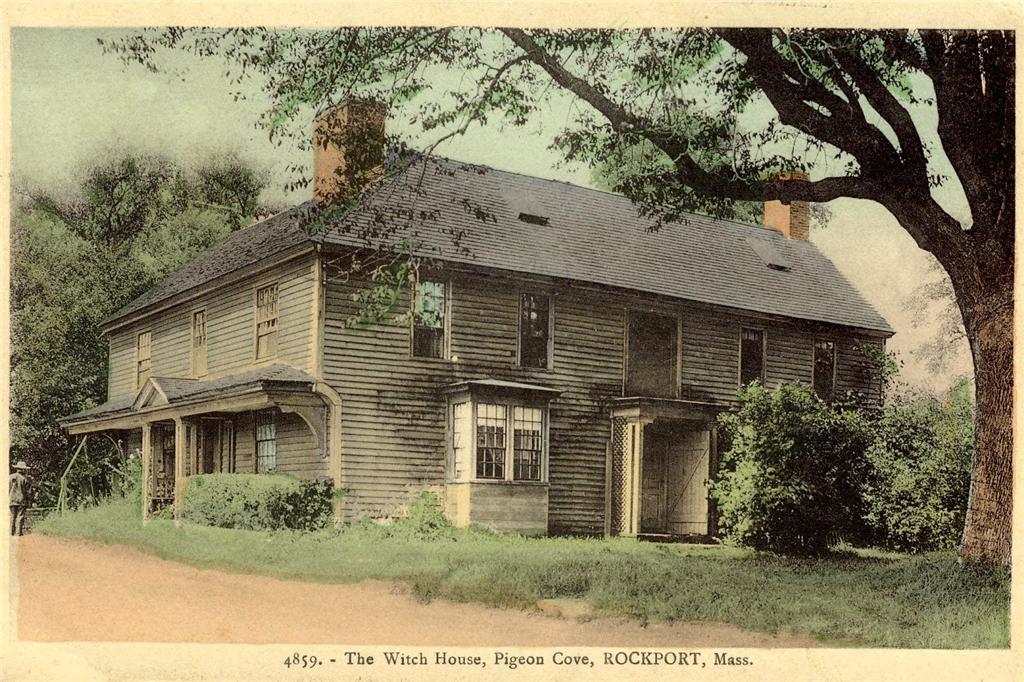

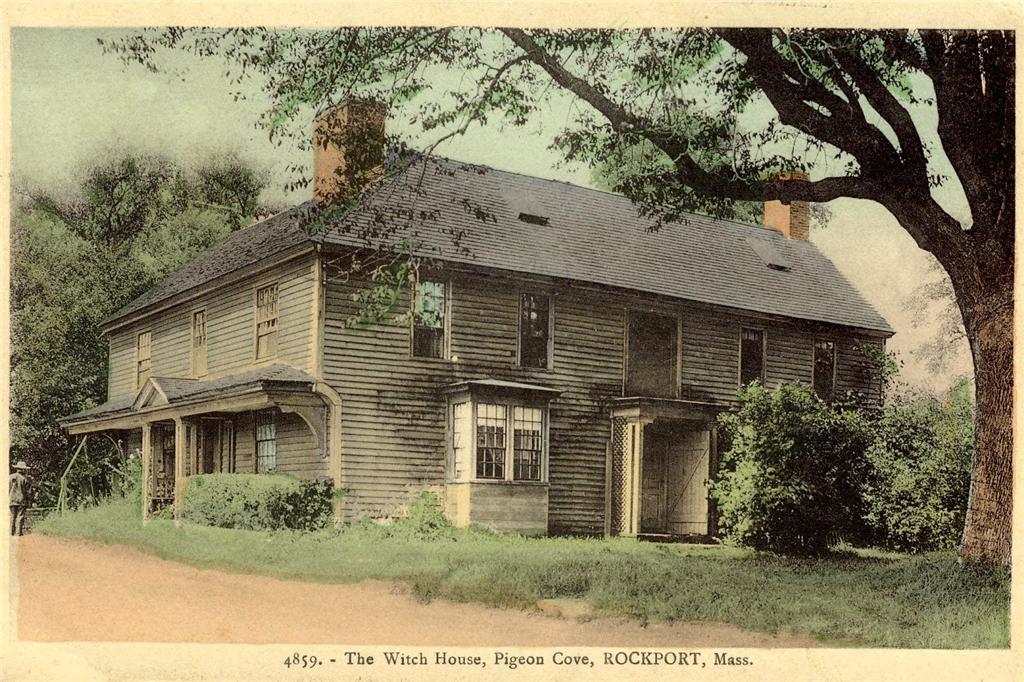

Skinner also tells us of "Miss

Wheeler, of Salem, who had fallen under suspicion, and whose brothers

hurried her into a boat, rowed around Cape Ann, and safely bestowed her

in the "the witch house" at Pigeon Cove."

"The Witch House, Pigeon Cove,

Rockport, Mass."

circa 1912

This seems to have more credence

(although I am not able to find any Wheelers involved in the hysteria)

for the simple fact that the Witch House still stands. It was also a

popular subject of postcards as early as 1905 under that name. The folk

memory of the event remains attached to the place, and adds weight to

the story. Also, just around the corner in Pigeon cove is a Devil’s

Den, a small boulder cave on the shore. Coincidence?

"Surf near the Devil's Den, Pigeon Cove

in Rockport, Mass."

The most famous escapees were

Phillip English and his wife. English was a well-to-do Salem Town

merchant. When the finger of accusation was pointed at him and his

wife, he didn’t bother to wait to see how it would all turn out in court

but simply skipped town to Boston until the hysteria had died down and

been buried.

In a sense, it was a turning

point in the whole affair. It was all well and fine if the lower ranks

of society, and a handful farmers and their wives were executed, but

when the fingers started turning towards the elite classes (for instance

when Governor Phips’s wife was accused),

the whole thing started grinding to a halt. Phips, for one, was not

amused, and the hangings were over.

Governor Phips, an ill-educated

fellow with "the manners of a 17th century sea captain,"

appointed upon arrival in May the special Court of Oyer (to hear) and

Terminer (to decide) to hear the witchcraft cases. Considered unfit for

his position, he did nothing to stop the witchcraft mania and executions

and only suspended the court in October after his own wife had been

accused.

Salem End Road: Building a Community

Having survived the winter in

the caves, the spring of 1693 brought new hope and a new start for the

Cloyes. Danforth gave them permission to build a house on his land and

that year they constructed a new house for themselves on Plantation

property.

Peter & Sarah Cloyes Homestead

Herring comments on the

location, "There was the Cowasock Brook**

nearby and a relatively friendly Indian village. Just across what

must’ve been a trail then

(now Salem End Road), there’s an enormous

glacial boulder you can see today that probably served as a good

landmark." This boulder is the

one that escaping families looked for.

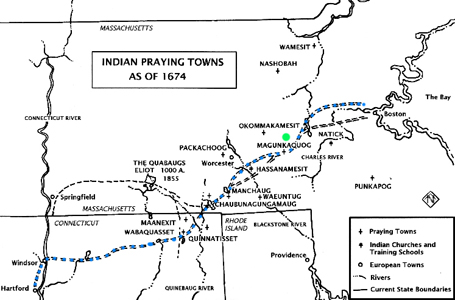

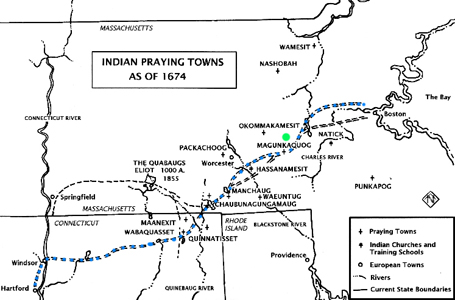

**

Cowasock Brook

was probably named after the Indians of the nearby

Praying Indian

Village of Magunkaquog, the "place of great trees" near Magunco

Hill in Ashland. It is possible this tribe still exists, as there

is a Pennacook Abenaki band in New Hampshire called the Cowasuck, the

"People of the White Pines." (Click

for the Cowasuck website.) The white pines are the tallest

trees in New England.

Danforth Plantation Boulder, Salem End

Road

The initial trickle of escapees

intensified to a migration, and by 1700 when Peter signed the township

petition for Framingham, at least 50 people related to the Towne sisters

had re-settled from the Salem Village area to the Salem End Road

district, with more than 800 acres given away to them by Danforth.

Among the new arrivals included the families of Sarah’s two sons from

her first marriage, Caleb and Benjamin, Benjamin arriving in the spring

of 1693, with Caleb following shortly thereafter.

Rebecca’s youngest son Benjamin

Nurse also relocated with his family in 1693, as did Mary’s son John’s

Easty and his family a few years later.

The Towne family was also

represented early in the migration. Lt. John Towne and his son Israel

Towne both relocated their families by 1698 and built on Danforth-gifted

land. Lt. John, one of Framingham’s original selectmen, was the son of

the Towne sister’s brother. Needless to say, grandniece Rebecca (Towne)

Knight did not join them in Salem End Road.

|

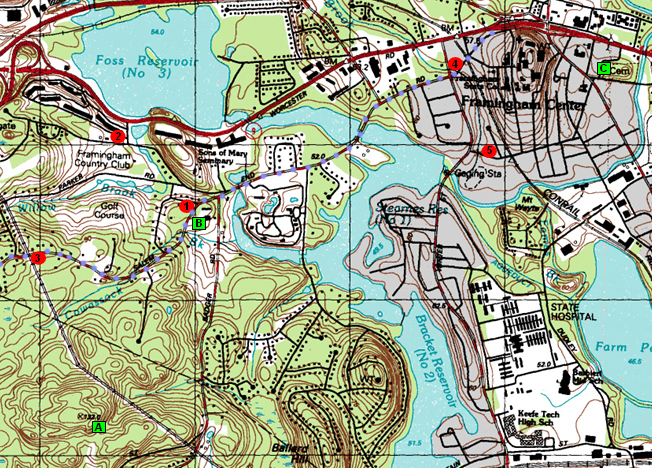

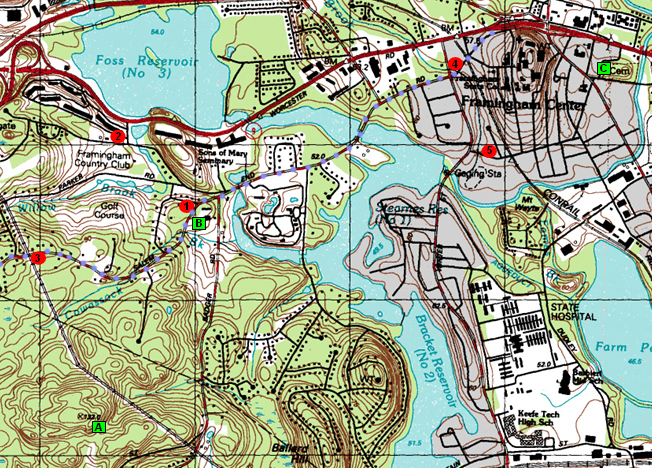

|

Map of Salem End Road Area

•

Red Dot #1:

Peter & Sarah Cloyes house

•

Red Dot

#2: Caleb Bridges house

•

Red Dot

#3: Benjamin Nurse house

•

Red Dot #4: Israel Towne house

•

Red Dot

#5: John Towne house

■

Green

Square #A: Witch Caves

■

Green Square

#B: Danforth Boulder,

signals

entering Danforth save zone

■

Green

Square #C: Framingham Old Burying Ground

•

Blue Dot

Road: Salem End Road

Click on map for large scale view |

The Nurses changed the spelling

of their name to Nourse to distance themselves from Salem, and if you

examine Framingham’s Old Burying ground, you will find many Towne, Nourse, Bridges, Easty, and Cloyes

names represented throughout the years. (One Cloyes, John,

was struck down

by lightening in 1777.)

Cloyes graves, and Nourse (Nurse)

family marker

Old burying Ground, Framingham

The Townes did not stay long in the area, but the other "witch"

names became part of the founding fabric and ongoing life of the town,

and descendents still live there. The earliest existing grave marker

left of the original émigrés is that of Benjamin Bridges who died in

1723. This marker, a rough field stone with the crudely cut epitaph,

reads, "When he served his generation, by the will of God he fell

asleep."

Benjamin Bridges, 3rd stone from left

click for

close-up

The Five Witch Houses of Framingham

Of the original escapees who

built in the Salem End Road community, a surprising five of these houses

still remain, representing 4 of the 5 families involved. Sarah and

Peter Cloyes’s 1693 house stands on Salem End Road. Caleb Bridges’

house is on Gates Street. The 1694 Benjamin Nurse homestead is on Salem

End Road. John Towne’s 1698 home is on Maple Street, and his son

Israel’s pre-1709 home stands on Salem End Road. Only the home of John

Easty is no longer standing.

Israel Towne house - Nurse Homestead -

Peter & Sarah Cloyes house

Salem End Road ~ Framingham & Ashland

John Towne house, Maple Street & Caleb

Bridges house, Gates Street

Framingham

Yet the Eastys were definitely

in Salem End early on. According to Hurd’s 1888 History of Essex

County, "The larger part of the [Easty] family moved to Framingham

after the execution of the wife and mother, hoping they had escaped the

laws of Massachusetts, but subsequently found that they were still in

the hated State; but they had cleared away too many fields to take up

stakes again, and have remained, some of them to this present day."

Three Sovereigns For Sarah

After the court of Oyer and

Terminer was dissolved, and all the witchcraft cases cycled through by

May of 1693, the processes of petitioning for compensation and

overturning the earlier verdicts began. At the fore of this effort was

Mary’s husband, Issac Easty. It took almost 20 years, but on October

17, 1710, the General Court passed an act that, "the several

convictions, judgments, and attainders be, and hereby are, reversed, and

declared to be null and void." Further, on December 17, 1711,

Governor Dudley issued a warrant awarding Issac 20 pounds sterling in

compensation for the injustice of the 1692 verdict against Mary. Mary’s

sister Sarah received 3 gold Sovereigns, each worth ¼ of a pound. Sarah

retrieved them herself, in her first and only return to Salem.

Gold Sovereign 1643 Charles I

60 shilling piece

Abigail Hobbs, Again

Having started with Abigail

Hobbs, the self confessed teen-witch of Topsfield, let’s finish with

her. In a strange and perverse twist, the damages paid in 1711 went not

only to the victims, but also to the accusers. Abigail, whose

obsession with being a witch and whose testimony was a nail in the

coffins of so many innocent people, was awarded 10 pounds sterling as "restitution."

Restitution for what?

Email Daniel V.

Boudillion

Back to Field

Journal

Copyright © 2007, 2009 by Daniel V. Boudillion

|

Gallows

Hill: Where Were the Witches Really Hung? by D. V.

Boudillion

Gallows

Hill: Where Were the Witches Really Hung? by D. V.

Boudillion